In order to help save a rare breed of Swiss goats, Bill and Casey Makela started using the animal's milk to

make an even rarer soap.

Nearly two decades ago, the Makelas adopted two Oberhasli goats and began looking for ways to preserve the breed not only

in the United States, but worldwide. They found the goats, milk makes rich moisturizing soap.

"Milk soap can be very difficult to make," Casey Makela said. "It's tough to get milk into the soap without ruining it."

Makela uses the milk from purebred Oberhasli goats in and effort to preserve and help the breed grow in the country.

The goats originated in Berne, Switzerland.

Six pregnant goats were imported to the United States in 1936.

Herd books closely tract the goats back to their ancestors still found in the Swiss Alps.

Non-pure versions of the Swill breed have become more common.

Despite the breed's medium size, the chamois or reddish-brown colored animals can produce up to two gallons of milk per day.

Goat's milk contains lactic acid with a butter fat content of nearly 4 percent.

When comparing the nutritional and compositional values of various types of milks, they differ little.

The fat content of goat and cow milk run about the same.

"Cow milk makes wonderful soap too. We use dairy goat milk because it becomes a preservation project.

We are able to work with a rare breed of dairy goats and make soap too." Makela said.

She makes her soap in the spring, summer and fall because the goats come into season to be bred in October.

She does not want to stress the goats while they are pregnant.

Even though Makela has a milk machine, she chooses to milk the goats by hand. She prefers to keep the entire process

of making soap as close to the way early settlers did it as possible.

"I just like the traditional value of going out and milking the goats by hand. Many of the things we do here today

as crafts were done here as part of daily life." she said.

Makela began perfecting her soap by researching the process of making soap as it has been done for thousands of years.

The origin of soap is not well documented, but appears to date back as far as 2000 B.C.

She became intrigued by the fact people did not use soap for cleaning themselves until the 18th Century. Up until then,

people did not consider cleanliness a positive virtue. Plagues drove people to use soap as a cleanser.

"I find the history of soap-making fascinating. Most people just didn't bath because they actually believed

it was unhealthy to use soap," she said.

Her soap-making processes closely reflects the methods developed by the United States's European settlers.

They used ash from cooking combined with beef tallow and pig lard.

She follows the lead of the settlers by using as many natural resources found on her farm as possible.

Settlers made soap in the spring using ashes collected from winter fires and grease left over from cooking.

"You have to think of times before the United States became industrialized. It's a fascinating history," she said.

Soap results from a fairly basic chemical reaction. While Makela could go on at length about the

process, most simply, she mixes fats and lye into a solution that saponifies to make soap.

|

|

The word "saponification" rolled off her tongue as she explained the chemical -- soap-making -- reaction. Saponification occurs when alkali mixes with caustic acids.

"The fat and caustic has to saponify to make soap. It's really cool," she said.

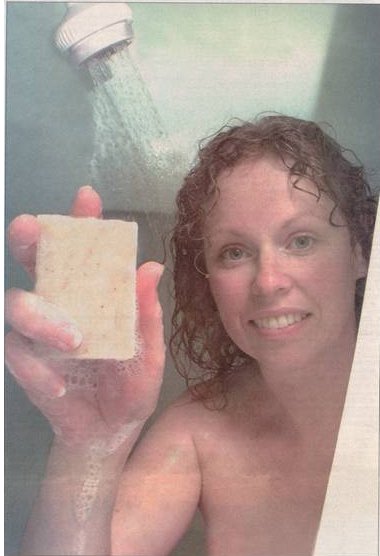

The liquid begins to thicken quickly. When she adds her milk, the fat and caustic bonds to capture and

protect the milk ingredient.

"The soap goes from a golden liquid to a lovely cream color," Makela said.

She pours the liquid into a mold where it takes the shape of a large 50 pound block. After about 24 hours, the soap becomes solid.

Makela uses a SUOMI Soap Cutter, which her husband invented and sells to other soaps makers. He used European models to design the cutter, but on a much smaller scale.

The cutter looks like a mechanical harp. She places the blocks of soap into the machine and pulls a large arm down causing several taunt wires to cut through it. She repeats the process until the blocks turn into hundreds of little bars of soap.

The Makelas enjoy music, and Bill uses his musical skills to make sure the wires are all equally taunt. He tightens the strings and then strums them like a guitar. When each string produces the same tone, he knows they are tight enough.

She cures the soap for about six weeks to let the compound stabilize into its bar shape. Curing causes excess moisture to evaporate, leaving behind one of the soap's best moisturizing qualities - glycerin.

"This is what makes natural soap so much different than the soap you buy in a store. Commercially produced soap is actually almost a by-product of real soap because most of the glycerin is taken out," Makela said.

Like commercially produced soaps, her soaps go through a year-long test process before being sold to customers.

Makela's interest in history led her to name her soap making company Killmaster Soapworks. The once thriving lumber town where she lives has become a ghost of its former existence.

While few people continue to live there, in the mid-1800's it included a large water-powered saw mill, a train stop, church and post office. She hopes by naming her business after the former town, the Killmaster name will live on for years.

"Our house was built in the late 1800's and my husband has been working to renovate it. We don't want to lose buildings you simply can't replace," Makela said.

Her historical surroundings have inspired many of her soaps. She makes several different kinds of scented soaps such as apple rose and honey oatmeal. She even produces a chocolate soap called Mackinaw Fudge.

Makela's Great Lakes Natural Soaps combine her history and soap making fascinations. She creates soaps tied to Michigan's past such as Paul Bunyon Bathe and Superior Suds.

In the future, the Makelas hope to private label soaps for historic sites such as lighthouses. The soaps's labels will include information about each historical site.

"With all of our Great Lakes soaps, we include a piece of history," Makela said. "I love being able to do this. I just love making soap."

|